[ad_1]

Framework is a little-known company that makes very good laptops that you can easily open and repair yourself. How easily, exactly? To find out, I dug around in the guts of a Framework Laptop 13 to swap in a new processor, louder speakers, updated hinges, and a much-improved display using just a screwdriver.

The process was a breeze, and I’m even more convinced that more laptop makers should get on board with the idea. Being able to upgrade individual parts instead of replacing the whole laptop is easier and cheaper for laptop owners, and it’s better for the environment, too.

In my years of testing, reporting, and writing about laptops, I’ve found that most have a typical lifespan of about five years. When they die, you have to buy a whole new one. But Framework’s laptops are designed to last much, much longer.

The company released its first fully repairable and upgradable laptop in 2021. It received a rare 10 out of 10 repairability score from iFixit, which means it’s one of the easiest laptops to fix, and we found that it was especially easy to open. In fact, the Framework Laptop 13’s repairability earned it a top spot in our guides to ultrabooks and business laptops.

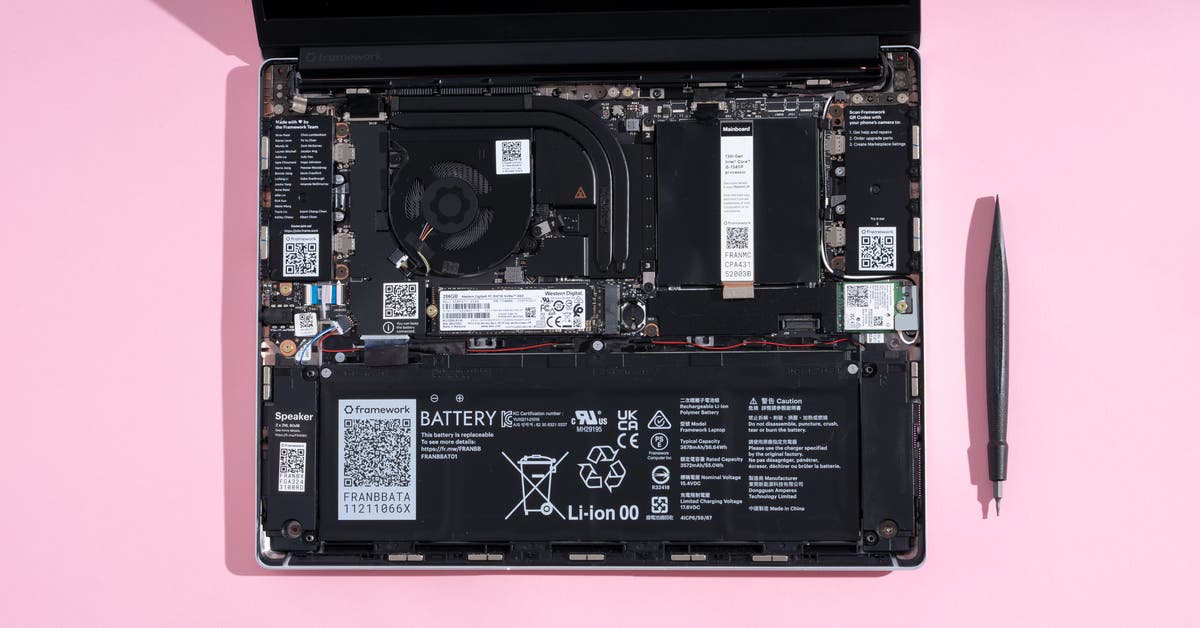

Inside, every part is labeled with handy QR codes that you can scan with your phone’s camera to read step-by-step replacement guides and find links to the exact parts you need. You can add storage and memory, replace the battery for around $70, upgrade to a new processor for $450 (or more depending on the processor you choose), and repair anything else if it breaks. Specialty parts—such as the mainboard, battery, a $40 touchpad replacement, a $20 speaker kit, and so on—are available only directly from Framework’s website, but you can get storage and memory upgrades from any retailer.

But there is a downside: If the company goes under, the Framework Laptop 13 becomes an ordinary laptop—when it gets old or breaks, you’ll have to replace the whole thing. So far, Framework has lived up to its promise: Each year since launch, the company has introduced upgraded parts, so Framework laptop owners can swap out older processors with the latest versions (among other upgrades).

When I upgraded a Framework Laptop 13 with the latest parts, using the included screwdriver and a helpful step-by-step guide, it took about an hour. (Be sure to have your BitLocker key and your Windows key handy. Sometimes when you upgrade parts, Windows locks access for security reasons. You need those keys to remind Windows that you are the rightful owner of this laptop.)

Upgrading the mainboard, battery, and display was much easier than I expected; each part swap took only 10 to 15 minutes each. It felt more like following Lego instructions—unplug a part, take it out, plug in the new part—than wrestling with a complex electronics project, aside from one tricky moment when I had to route wires while upgrading the laptop’s hinge. Most owners will never need to swap out a hinge, but I appreciate the option—one of my college laptops died to a busted hinge (RIP) after my uncle tripped over the power cable and the open laptop took a tumble. I could have saved a lot of money by replacing it myself rather than buying a whole new computer.

My Framework experience left me wondering: If it’s better for both buyers and the environment, why doesn’t every company make laptops so easy to repair and upgrade?

Why aren’t more laptops easily repairable?

Some companies have tried to create repairable devices—the Fairphone is a notable success, though it’s available only in Europe—but so far, most have failed to produce repairable laptops. For instance, after releasing an upgradable gaming laptop, Alienware never followed through on releasing replacement parts. Other companies continue to try: Lenovo’s working on a repairable laptop dubbed Project Aurora, which hasn’t advanced beyond the concept stage yet. And Microsoft just announced that it will sell replacement parts for its Surface laptops; this is certainly a step in the right direction, though Surface laptops aren’t quite as easy for the average person to fix themselves as Framework’s machines.

Dell announced Concept Luna, a repairable and upgradable laptop similar to the Framework Laptop 13, back in 2021. But more than two years later, the company hasn’t actually launched a product, and Katie Green, Dell Technologies’s sustainability strategy product lead, confirmed via email that the company does not have any plans to do so in the near future. Green said that Concept Luna has provided Dell “with insights into more recyclable designs and energy savings throughout our portfolio.” But she added: “Bringing a solution like Concept Luna to market entails enabling and integrating the services and business model that surround it.”

What exactly does that mean? We spoke to several experts about the challenges of designing and selling a fully repairable and upgradable laptop. Elizabeth Chamberlain, iFixit’s director of sustainability, told me that “repairability creates some design constraints.” A lot of companies design thin and light laptops by gluing and soldering pieces together, which makes them harder to upgrade and repair. But Framework has already proved that it’s possible to create a durable, thin-and-light laptop that’s easy for regular people to fix at home.

To Framework CEO Nirav Patel, it’s also about the money. “This is less a design challenge than it is a business model choice,” Patel said. “Consumer electronics companies’ revenues are driven by replacement cycles. Designing products to last longer, and reducing waste as a result, cuts directly into their existing revenue streams and harms their business model.”

Linn Huang, IDC research vice president of devices and displays, agreed that it makes “more fiscal sense to sell an end user a new notebook every four years instead of a new component every other year.”

But Framework’s business model may actually pay off. Patel said that, as of early 2023, Framework is one of the only laptop companies growing while all other manufacturers are seeing steep declines in laptop sales. The recent drops are largely the result of “record growth” in 2020 and 2021, said IDC’s Huang, as people scrambled to buy laptops during the pandemic peak of remote work and schooling. Those laptops are only two to three years old now and don’t yet need to be replaced. Weaker consumer spending is another reason behind other laptop makers’ declines, according to Huang. But despite those larger economic forces, Framework’s business is doing well—so far.

Why you should be able to repair your tech at home

Questions surrounding whether Framework’s business model is a (financially) sustainable one aside, there’s no denying that one of the most effective tools for reducing carbon emissions is to buy fewer things—and to make the things you already have last longer. That also keeps e-waste and plastic out of landfills and reduces mineral extraction at a time when global demand for minerals is increasing. Multiple experts have told me that the best way to shop more sustainably is to use what you already have as long as possible. More repairable tech devices would go a long way toward achieving that goal.

“Everything eventually breaks,” iFixit’s Chamberlain said. But imagine a world in which you could take 30 minutes to swap out a depleted battery or a damaged screen instead of having to buy a brand-new device.

Framework is one of the few companies putting repairable devices into people’s hands, and if the right-to-repair movement succeeds, others might be legally compelled to make it easier to fix your tech at home. “We see the same problems around closed, unrepairable products across every part of consumer electronics,” Patel said. “We started with laptops, but we’re fundamentally not only a laptop company. We’ll be taking our product philosophy and mission across consumer electronics, one category at a time.”

This article was edited by Caitlin McGarry and Arthur Gies.

[ad_2]